What on earth is Connectomics

Whether or not you heard about the term, you definitely heard about the scientific conundrum behind connectomics: how do networks of billions of neurons and trillions of connections in our nervous system produce actions, thoughts, emotions and memories? Well, connectomics aims to answer just that! By means of advanced neuroimaging techniques including, most notably, electron microscopy and functional magnetic resonance imaging, the goal is to map connectomes of human and non-human animals, to unravel the structural basis of behaviour.

What is a connectome, you ask? Put simply, a connectome is the complete set (ome) of neural connections in a central nervous system. The addition of the suffix omics simply indicates the study of an ome, so that’s connectomics, the in-depth study of biological systems’ connectomes. Now that we got etymology & definition out of the way, let’s answer the big questions: how do we even build a connectome; what does it tell us and why is all that useful?

The first step in building a connectome is finding an organism worthwhile exploring. The human brain is the obvious choice here, however, I’ll explain shortly why this isn’t the most popular one. Notable examples of non-human animal models include the fruit fly Drosophila, the roundworm C. elegans and the mouse. The next step is to map the central nervous system (CNS) of your model of choice. This can be done in one of two ways:

-

Via Electron Microscopy (EM), where tissue is sliced into very thin sections (~4nm) and scanned via an electron beam that can reach resolutions of up to 10nm, allowing us to distinguish morphology, organelles and even individual synapses. Using this data, one can reconstruct the complete set of neural connections within a CNS into a comprehensive 3D map (such as the one in the image above), that packs valuable anatomical and connectivity-related information. This is especially useful when inferring the role of restricted neural pathways in specific behaviours.

-

The second option is via Functional magnetic resonance imaging (or fMRI), which measures brain activity according to changes in blood flow, such that increased blood flow in one region indicates increased activity in the area of interest.

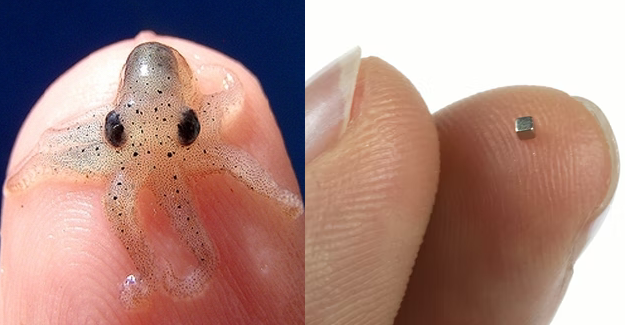

EM data tends to be preferred for its high resolution, but acquiring an EM volume and turning it into a comprehensive 3D map is no mundane task. I’ll describe this technique in further detail at one point, but to paint the picture: it takes the best electron microscope today approximately 1 year to image 1 cubic millimetre. This is roughly the size of a pygmy squid brain (below is an image of both for reference).

So for small, simple organisms like C.elegans, with roughly 300 neurons and 7,600 synapses, reconstruction was possible early on. In fact, the first-ever fully mapped connectome was that of C.elegans back in 1986 (John White and colleagues at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, University of Cambridge), and you can find this data here. Subsequently mapped (though incompletely) connectomes include the zebra fish (100 000 neuronst; at Max Planck Institute), the bumblebee (1 million neurons), the locust, and, an animal that has received a lot of attention across scientific disciplines, the fruit fly Drosophila(with 100 000 neurons).

When it comes to humans, EM is unfortunately not the best option at present, for 2 main reasons: 1st, brain preparation for imaging requires living samples, and 2nd the human brain is so huge it would take a very long period of time to acquire sizable data. Since 1 mm³ takes about a year to image, and the human brain has roughly 1.3 million mm³, that means it would take about 1.3 million years to have the entire brain mapped by EM; and that’s without reconstructing the connectome (86 billion neurons and about 100 trillion connections). But suppose we had that data at hand, genetically manipulating human brain cells to link them to a specific function still wouldn’t be ethically feasible.

For this reason, fMRI is the current state of the art technique when it comes to human connectome data. The mission of mapping the human brain is currently pursued by The Human Connectome Project: the first large-scale attempt to collect connectomics data from individuals in vivo. Although this technique does not reach nearly as high resolutions as EM, its discoveries are very much noteworthy.

Since bridging the gap between neural structure and function is a central dogma in neuroscience, you can imagine that connectomics will have important implications for two major fields: medicine and computation. Connectomics is a useful tool to unravel the structural causes of neurological disease and to gain insight into psychopathologies. In addition to that, connectomes help us develop computational models of whole-brain dynamics which can contribute to AI ai and Machine learning (e.g. algorythms implemented by biological brains can be appied to graphs) (P.Vogels et al., Mullakaeva et al., J Brown, et al.).